The first report of blepharospasm in the medical literature was in 1870 by Talkow,4 followed by Meige.5 Most authors now believe that facial dyskinesias arise from an organic basis.6,7 Nonetheless, debate persists in the literature regarding the role of psychiatric illness, particularly obsessive-compulsive disorder, in the development of blepharospasm.8–10 Treatments for belpharospasm were first developed in the mid-twentieth century, consisting of selectively sacrificed branches of the facial nerve. These treatments had reasonable success but resulted in a multitude of complications. Most of these treatments have now been supplanted by safer and minimally invasive techniques, most notably botulinum neurotoxin injections.11

Fundamental Science

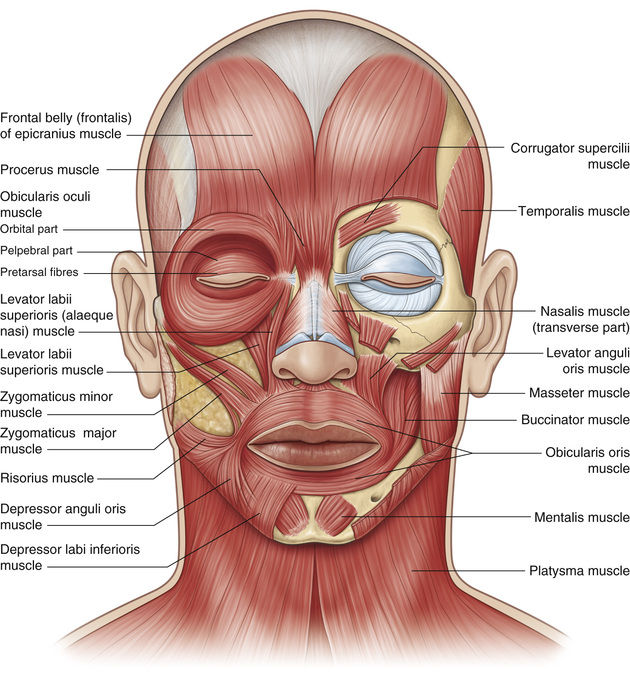

Dystonia is a hyperkinetic movement disorder, resulting from an abnormal balance between agonist and antagonist muscles. It is thought to involve a loss of inhibition, abnormal plasticity, and sensory dysfunction.12 Facial dystonia includes blepharospasm, apraxia of eyelid opening, Meige syndrome, hemifacial spasm, and aberrant regeneration of the facial nerve, each characterized by involuntary spastic activity in the periocular protractors, mainly the orbicularis oculi and corrugator muscles, but also affecting other facial muscles13 (Fig. 32.2).

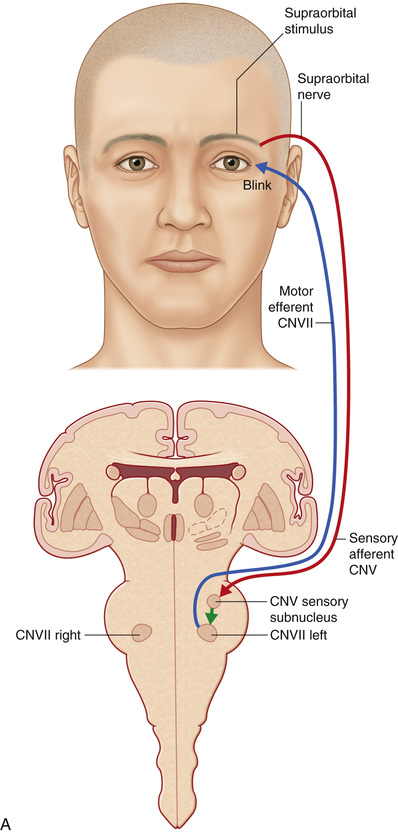

Stimulation of the supraorbital area, conjunctiva, or cornea generates an early ipsilateral or a late bilateral eyelid blink reflex via an afferent impulse that travels in the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve to its sensory nucleus, which projects to the motor nucleus of the facial nerve. The supraorbital skin impulses travel along the supraorbital nerve, whereas the corneal and conjunctival afferents travel along the long ciliary branch of the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve.14 The early blink reflex pathway is conducted through an ipsilateral, oligosynaptic arc in the pons from the supraorbital branch of the sensory trigeminal root to the ipsilateral facial nucleus. The late blink reflex and corneal reflex are conducted through polysynaptic pathways in the lateral reticular formation of the lower brainstem, from the descending spinal fifth nerve nucleus to the ipsilateral and contralateral facial nucleus, which innervates the orbicularis oculi muscle, causing the blink.14 Because of this bilateral innervation, the reflex should generate a bilateral blink response (Fig. 32.3).

In some patients, blepharospasm may be secondary to irritating eye disease such as dry eye, iritis, corneal ulceration, keratitis, or other form of ocular surface disease that initiates a reflex arc from the cornea, conjunctiva, or supraorbital area along the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve to the facial nucleus. However, when ophthalmic examination does not reveal a structural cause for this so-called secondary blepharospasm, the involuntary closure of the eyelids is described as neurologic blepharospasm, which is a primary disorder of the blink reflex mechanism controlling the frequency and intensity of orbicularis oculi muscle contraction.3 This condition is known as benign essential blepharospasm (BEB).

The cortical control of eyelid closure is not well understood. Recent studies have shown involvement of the cingulate and primary motor cortices,15 as defined in transcranial magnetic stimulation mapping16 and functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)17 studies. Similarly, the pathology in the primary dystonias is also not well understood, and some suggest that the pathology originates in the basal ganglia or brainstem, although definitive evidence to support these assumptions is lacking.18 Neurophysiologic testing has shown that the neuronal arcs of the facial reflexes in blepharospasm are normal. Instead, a deficit in supranuclear control of motorneurons and interneurons from the basal ganglia is thought to mediate the abnormal muscle contractures in BEB.14 Positron emission tomography neuroimaging has shown patterns of abnormalities involving several cortical and subcortical areas that control blinking, including the inferior frontal lobe, caudate, thalamus, and cerebellum.19,20

Benign Essential Blepharospasm

Epidemiology

BEB has a prevalence of 3 to 13 per 100,000 with a 3 : 1 female predominance, although most prevalence studies use treatment-based data and thus likely underestimate its true prevalence.12,21–25 BEB typically presents in the fifth to seventh decades of life, although men with primary BEB tend to develop symptoms at an earlier age compared with women.26 Interestingly, studies have shown a caudal-to-rostral shift of the site of onset of the dystonias, with writer’s cramp having the earliest onset at 38 years, followed by cervical dystonia at 41 years, spasmodic dysphonia at 43 years, and BEB at 56 years.27

Environmental factors in the development of BEB have been evaluated. A study in an Italian population suggested an inverse relationship between coffee consumption and the development of BEB, with the prodopaminergic activity of caffeine cited as a likely protective agent.28 It is this same action of caffeine that is believed to be protective in the development of Parkinson disease (PD).29,30 Although there is evidence of smoking being protective against PD,31,32 this relationship was not found for blepharospasm.28 A direct genetic relationship for BEB has not been shown, but the largest study to date on the genetic basis of dystonias supported an autosomal dominant transmission pattern with reduced penetrance of about 20%.33 This study showed a heterogeneous phenotypic appearance of dystonia within families, supporting a common causality to this group of disorders.

Pathogenesis

The etiology of BEB is multifactorial but likely centered on the basal ganglia, which is thought to be the central control center for blinking. Neuropathologic studies in BEB have shown loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra.34–36 The blink reflex arc consists of an early ipsilateral first response (R1) and a late bilateral second response (R2). The R1 reflex can be inhibited by a response from the levator palpebrae muscle to achieve normal eyelid position. The impulses for R1 and R2 are mediated through the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve to the pons and subsequently connect with the motor facial nerve nucleus, but they can also be influenced by the cortex and basal ganglia, as described above. Electrophysiologic studies have shown increased amplitude and duration of the R1 and R2 responses, suggestive of increased brainstem interneuron and motor neuron excitability secondary to supranuclear input.14,37,38

Ophthalmic disorders such as dry eye, conjunctivitis, and uveitis may act as afferent triggers, resulting in secondary blinking that stimulates abnormal interneuron excitability as a result of induced trigeminal hypersensitivity.39,40 Photophobia occurs in up to 80% of patients with BEB, triggering the eyelid spasms via a neurologic positive feedback loop containing overactive spinal interneurons that stimulate the cervical sympathetic chain.11,41

Classification

Blepharospasm may be classified as a primary disorder of the blink reflex mechanism pathways described above, or it may be secondary to ophthalmic disorders that trigger hyperexcitability in the blink reflex. Finally, blepharospasm may result from focal brain lesions in key neurologic structures important to eyelid movements, including the thalamus, cerebellum, dentate nucleus, cerebellar peduncle, midbrain, lower brainstem, and basal ganglia. When a structural cerebral lesion is the cause for blepharospasm, stroke has been the most common etiology, followed by vascular malformation and cystic lesions.42 However, lesions would be unlikely to cause isolated blepharospasm; rather, they would be associated with other neurologic deficits.

Clinical Features

BEB is an involuntary, bilateral, and symmetric spasm of the orbicularis oculi muscles and leads to partial or total eyelid closure. Symptoms begin unilaterally in 25% of patients, but they become bilateral in almost all cases.43 The bilaterality helps distinguish BEB from hemifacial spasm. The spasms may be tonic and sustained, brief and clonic, or regular and rhythmic. Patients may complain of retro-bulbar pain during spasms.44 Spasms associated with lowering of the brows below the superior orbital rim is a distinctive clinical finding. This finding is known as the Charcot sign and indicates intense contraction of the orbital portion of the orbicularis oculi muscle and helps differentiate it from apraxia of eyelid opening. This contraction may be so forceful and complete as to render the patient functionally blind for substantial periods of the day. Particularly when performing tasks such as driving or navigating a busy street, this involuntary eyelid closure may result in injury to the patient or others. BEB is often associated with dystonia in other body parts. A recent study on patients with BEBfound that 50% had pure BEB, 31% had BEB as part of Meige syndrome, and 4% had BEB with apraxia of eyelid opening.45

In BEB, the blink rate is increased and the spasms may be brief or prolonged. It is a chronic disease that can progress over a period of months to years.25,46 Patients may identify a number of precipitating triggers, including bright lights, automobile driving, chewing, speaking, stress, or voluntary muscle contraction. Clinically, touching the periorbital area may precipitate spasms. In contrast, symptoms are often reduced by attention-demanding tasks such as writing, singing, yawning, or whistling,18,44,47 and patients may learn to use these “tricks” to conceal their spasms. Sleep and relaxation have also been shown to relieve the symptoms of blepharospasm, in contrast to hemifacial spasm in which the spasms persist (see Hemifacial Spasm section).43 Importantly, patient attention or concentration during a doctor’s examination may also lessen the severity of blepharospasm. The clinician must take care not to underestimate or dismiss the patient with minimal symptoms during examination.

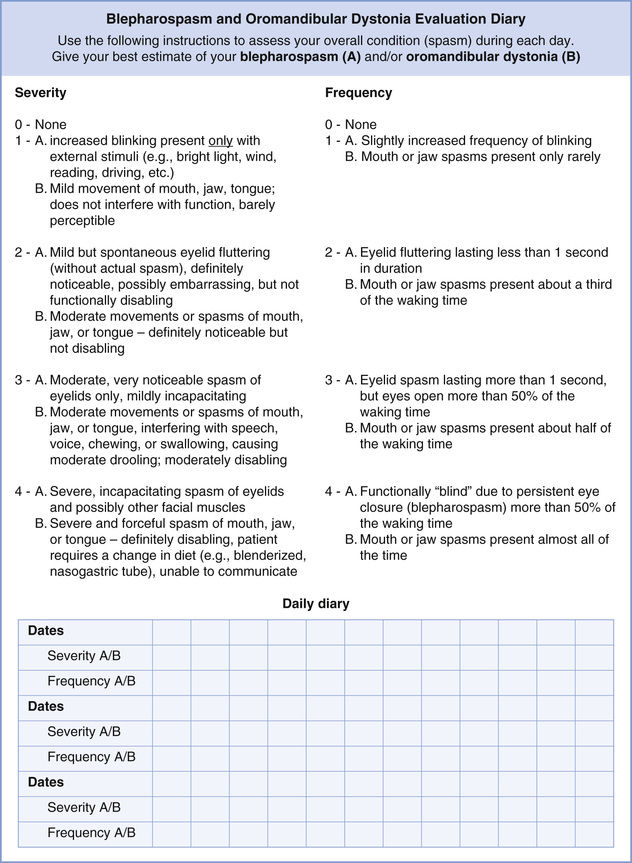

Clinical evaluation and severity scoring of BEB can be challenging because of the subjective nature of the disease. The only grading scale specifically developed for BEB had long been the Jankovic rating scale (Fig. 32.4).48 This scale includes a severity score and a frequency score based on a five-point grading system. However, it lacks a clear definition of spasms, including degree, duration, and frequency.46

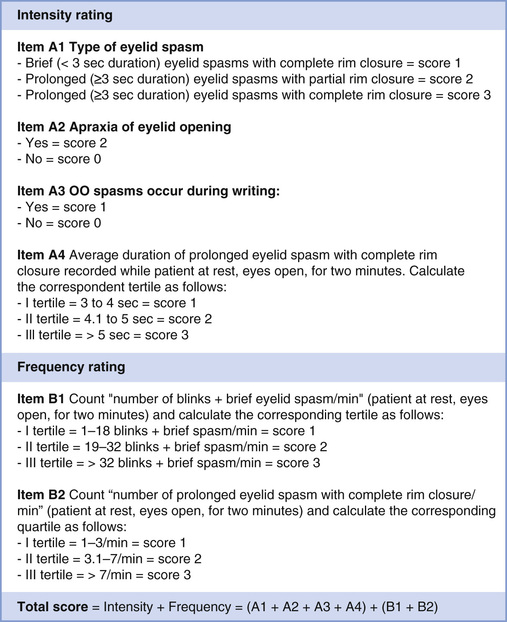

Recently, a new severity scale was developed and validated for BEB (Fig. 32.5).46 This scale consists of six clinical items. The core clinical hallmarks of BEB severity are (1) degree of eyelid closure, (2) duration of eyelid closure, and (3) frequency of spasms. Additional features captured in the scale include (4) blink rate, (5) apraxia of eyelid opening, (6) and lower face spasms. Spasms are defined in this scale as brief (<3 seconds) or prolonged (≥3 seconds) and leading either to incomplete or complete palpebral fissure closure. Most of these items can be easily measured during a brief clinical examination, although the accuracy of measurements could be improved with video recording. This scale has good internal consistency and satisfactory clinimetrics. Comparison of total severity scores before and after BEB treatment may be a useful clinical tool for treatment efficacy. One limitation of this severity scale is a failure to incorporate eye symptoms such as dry eye and photophobia.

As described earlier, up to 80% of BEB patients experience photophobia, and 40% to 60% of patients experience dry eye before or at the onset of BEB.39 Studies have shown that BEB may play a role in the progression of inflammation in dry eye and that treatment of BEB may effectively alleviate the symptoms.49

Investigations

Blepharospasm is a clinical diagnosis. Once established, no imaging or serologic workup is required. However, if the symptoms appear to be unilateral rather than bilateral, the diagnosis of blepharospasm should be called into question and neuroimaging obtained to rule out hemifacial spasm (see Hemifacial Spasm section). Similarly, if blepharospasm is associated with other neurologic deficits, neuroimaging should be obtained to rule out cerebral lesions.

Management

The gold standard treatment for blepharospasm is chemodenervation of the orbicularis oculi muscles with botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT). Alternative treatments include oral medications, physical measures, topical and surgical interventions, as well as behavioral and environmental changes.

Botulinum Neurotoxin

In 1989, blepharospasm became the first indication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the use of BoNT, and its success was attributed to its efficacy and low side-effect profile in a disease that had previously been difficult to treat. (See Chapter 33, Neurotoxins and Their Applications for details regarding history, subtypes, and mechanism of action of BoNT.)

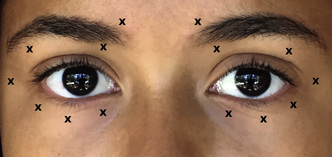

BoNT controls or minimizes eyelid spasms in some 80% to 90% of patients but does so temporarily, with the clinical effect waning in 8 to 16 weeks. Up to 92% of patients receiving BoNT can expect long-term efficacy with repeated injections.50 A common injection scheme is depicted in Fig. 32.6. The injections in the upper eyelid are often placed temporally and nasally in the eyelid, avoiding the central eyelid and the underlying levator palpebrae superioris, to reduce the risk of ptosis. Arguably, ptosis may be prevented by ensuring that BoNT injections are placed in a preseptal plane, even if they are placed in the central eyelid.

Loss of effectiveness, or tachyphylaxis, after multiple BoNT injections is rare but thought to result from the formation of neutralizing antibodies.51 These antibodies are most likely to form after booster injections 2 to 3 weeks after initial injection.12 Boosters, therefore, are no longer recommended. The formulation of Botox was changed in 1997 to reduce the protein content and thereby the formation of neutralizing antibodies. IncobotulinumtoxinA (Xeomin, Merz Pharmaceuticals, Germany) was designed free of complexing proteins for this reason. A small percentage (~2%) of patients have reportedly experienced remission after BoNT treatment, requiring no further intervention.52

Adverse effects from BoNT, which are minimal and transient, include pain on injection, incomplete blink, ptosis, accentuation of lower eyelid ectropion or entropion, decreased lacrimal pump function with dry eye symptoms and, rarely, corneal erosion.52

Oral Pharmacotherapy

Oral pharmacotherapy for BEB has shown inconsistent and unsatisfactory results. Moreover, systemic therapy has a much higher risk of systemic adverse effects compared with local BoNT injections. However, in patients refractory or resistant to BoNT injections and who want to avoid surgical treatment, oral therapy may be attempted with medications mostly from the neuroleptic class, including gabapentin, diazepam, clonazepam, baclofen, carbamazepine, levodopa, carbidopa, trihexyphenidyl, lithium, and benztropine. One prospective study showed a persistent benefit in only 22% of BEB patients, and the response was best with clonazepam.43 Determining the correct dose of oral pharmacotherapy may be a tedious process. The dose should be individualized and titrated to the lowest effective dose and each trial observed for 1 to 2 months to assess response. One starting protocol includes clonazepam 0.5 mg by mouth three times daily.

Surgical Management

Although most patients respond well to BoTN for management of blepharospasm, up to 4% of patients may have intolerable side effects or insufficient effect.53 Surgical options include eyelid protractor myectomy, differential section of the facial nerve branches, and frontalis suspension.

In eyelid protractor myectomy, the orbicularis oculi, corrugator supercilii, and procerus muscles are excised in a subtotal fashion. Approximately 50% of patients treated with eyelid protractor myectomy do not need BoNT injections at up to 5 years after surgery, although the need for postoperative BoNT is higher if the patients had preoperative BoNT.54 For patients receiving BoNT postoperatively, 55% thought the BoNT was more effective after surgery and 36% required injections less frequently.55 Additional advantages of myectomy include ability to concomitantly treat blepharoptosis, brow ptosis, and dermatochalasis, which are common concomitant conditions in patients with blepharospasm.55 Complications from surgical myectomy are infrequent but include lagophthalmos in 18.5%, hematoma in 2%, and skin necrosis in 2% of patients.54 Lagophthalmos can be treated with ocular lubrication, although the study showed that 20% of these patients required release of upper eyelid adhesions and 2% required a lower eyelid tightening procedure. The other complications resolved without sequelae.54

Differential section of the facial (seventh) nerve (DSSN) may be considered for patients who have failed more conservative treatments, including BoNT and eyelid protractor myectomy. In fact, myectomy may fail to control blepharospasm in up to 21% of patients,13 and in these patients, DSSN can be considered. In this procedure, the branches of the facial nerve are stimulated to determine which to ablate for treatment of BEB. Often, destruction of the zygomatic branch is required.13 This procedure reportedly achieved long-term alleviation of symptoms in up to 75% of patients after either one or two DSSN procedures.13,56 Surgical complications from DSSN are relatively high and include paralytic lower eyelid ectropion in 25% to 44% of patients.13,56 Other paralytic complications have been seen in 35% of patients undergoing DSSN and include brow ptosis with accentuated upper eyelid dermatochalasis, upper lip paresis, and drooping of the corner of the mouth.56

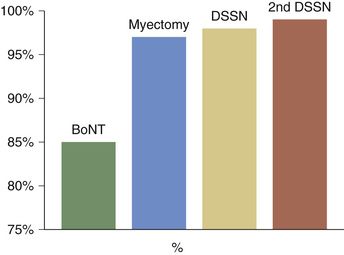

Some patients not responding fully to BoNT injections may benefit from adjunctive treatments.52 In a cohort of patients with BEB treated in a stepwise fashion with BoNT, protractor myectomy, and DSSN, success rate was 85% for BoNT only; 97% for BoNT and protractor myectomy; 98% for BoNT, protractor myectomy, and DSSN; and 99% for BoNT, protractor myectomy, and two DSSN operations (Fig. 32.7).13

Frontalis suspension has also been advocated for management of BEB, and it is most effective in patients with apraxia of eyelid opening (see Apraxia of Eyelid Opening section). Other treatments have included chemodenervation with doxorubicin injections, oral pharmacotherapy with trihexyphenidyl, benztropine, clonazepam, diazepam, and haloperidol, but these treatments have poor success when used alone. Finally, behavior therapy combined with hypnosis and biofeedback have been described.52 Surgical fixation of the supraorbital frontalis being explored by one surgeon as a method to control sensory feedback that may stimulate orbicularis spasms.3

Disease Course, Complications, and Prognosis

BEB is a chronic disease that can progress over a period of months to years.25,46 The spasms may interfere with visual function, cause ocular discomfort, and reduce vision-targeted health-related quality of life (HRQOL). Patients with BEB reported ocular pain and visual task difficulty with driving and near and distance vision, underscoring that everyday performance abilities from the patient’s perspective are compromised by this condition.25 The HRQOL scores of patients with BEB are comparable with the scores of patients with major chronic eye diseases such as diabetic retinopathy, age-related maculopathy, glaucoma, and cataract.

BEB may be associated with other craniocervical dystonias, including lower facial, masticatory, lingual, pharyngeal, laryngeal, or cervical dystonia, and involvement of the lower facial and masticatory muscles becomes fairly common in patients with blepharospasm. One study showed that 50% of patients evaluated for BEB had isolated BEB, 31% had BEB as part of Meige syndrome, 4% had BEB as part of apraxia of eyelid opening, and the remaining 15% had BEB with one or more other facial dystonias.45 Of the focal dystonias, BEB has the highest probability of spread, at about one-third of patients. The probability of spread is highest within the first 3 years after dystonia onset, and older age of onset, female gender, and history of head trauma may increase the risk of spread.57–60

Although some authors claim a psychiatric component in the etiology of BEB, there is no scientific evidence to support these assertions.25 Conversely, a number of studies have shown that BEB has a substantial effect on mental health. In fact, patients with BEB reported high rates of depressive and anxiety symptomatology related to their disease.25,61 Interestingly, the HRQOL scores did not improve in patients after successful BoNT treatment.62 One postulated reason for this finding is that the symptoms of BEB are rarely cured and almost always return between treatments. The anticipation of recurring symptoms as the treatment effect wears off may cause patients continued anxiety and depressive symptoms. These findings underscore the disabling ramifications of BEB even in the face of otherwise normal visual acuity and fields. Physicians who treat BEB must be prepared to provide appropriate patient counseling and mental health support as work goes on to identify better and more permanent treatments for this disabling condition.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree