and Osama Ibrahim1, 2, 3

(1)

Roayah Vision Correction Center, Alexandria, Egypt

(2)

Alexandria University, Alexandria, Egypt

(3)

International FemtoLASIK Centre (IFLC), Cairo, Egypt

21.1.1 Surgical Technique

21.1.2 Results

21.1.3 Topographic Changes

21.2.1 Treatment Parameters

21.2.2 Surgical Procedure

21.2.3 Results

21.3.2 Surgical Procedure

21.3.3 Results

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this chapter (doi:10.1007/978-3-319-18530-9_21) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

An erratum of the original chapter can be found under DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-21221-0_23

An erratum to this chapter can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-18530-9_23

As mentioned earlier in this book, SMILE has shown great efficacy and accuracy in normal corneas, having its unique and special advantages over any other refractive techniques, being flapless and less invasive. Furthermore, the ability to tailor and center the procedure as required within the cornea, together with better biomechanical stability [1], made SMILE a reasonable technique to deal with special cases which will be discussed in this chapter.

21.1 Combined SMILE and Cross-Linking (CXL)

Moones Abdalla4, Ahmad El Massry4, Assem Zahran5, Eman El Maghraby5 and Osama Ibrahim5

(4)

Roayah Vision Correction Center, Alexandria University, Alexandria, Egypt

(5)

Organisation Name, City, Country

Theoretically, SMILE has biomechanical advantages over LASIK because it does not involve the creation of a flap and leaves the stroma over the lenticule almost untouched, making it a procedure with minimal alterations of corneal biomechanics [2, 3]. However, there are not many published studies regarding these biomechanical benefits of SMILE.

In SMILE, the refractive stromal tissue removal takes place in deeper stroma, leaving the stronger anterior stroma intact, thus leaving the cornea with greater tensile strength than LASIK for any given refractive correction [4, 5]. Based on Randleman’s data, the model predicted that the postoperative tensile strength after SMILE was approximately 10 % higher than PRK and 25 % higher than LASIK [6].

We anticipated that combining SMILE with intrastromal collagen cross-linking (CXL) would add to the safety, predictability, and stability of SMILE alone when conventional laser vision correction is not favored because of suspicious topography and or thin corneas . Furthermore, we reasoned that combining CXL with SMILE in eyes with forme fruste keratoconus (FFKC) or early keratoconus could strengthen the cornea to stop the progression of the ectatic disease while meeting patient demands for improving unaided vision. This prospective study included 34 eyes of 18 patients suffering from myopic astigmatism, with topography not suitable for LASIK or diagnosis of FFKC, moreover we included patients with a stable refraction and topographic findings for at least 1 year, CDVA > 0.7 (Snellen decimal), central corneal thickness >460 μm, and patient age >21 years.

21.1.1 Surgical Technique

SMILE was performed using VisuMax ® 500 kHz laser (Carl Zeiss Meditec AG, Germany). All cases had a 100 μm cap and a minimum of 300 μm of residual stromal bed. Intra-pocket injection of isotonic riboflavin three times with a 5 min interval was followed by 5 min of UV irradiation using 18 mW/cm2. Biomechanical stability was assessed using the Corvis ® ST (Oculus GmbH, Germany), measuring and correlating IOP and deformation amplitude.

21.1.2 Results

Mean patient age was 29.4 ± 5.63(22–35). Mean preoperative refraction was −3.97 ± 1.87 D sphere (range −6.0 to −1.25) and −2.85 D cylinder (range −0.75 to −4.25). Mean postoperative spherical refraction was −0.14 ± 0.73 D (range −1.25 to +1.5) and mean astigmatism was −0.38 ± 0.45 D. Seventy-two percent was within ±0.5 and 89 % within ±1.0 D at the end of the follow-up. The change in the mean UCVA is shown in Fig. 21.1. Delayed recovery of visual outcome was noticed due to haze, which was found to improve 1–3 months after surgery.

Fig. 21.1

Uncorrected visual acuity change (decimal) during the follow-up time

21.1.3 Topographic Changes

Example 1 (Fig. 21.2)

Fig. 21.2

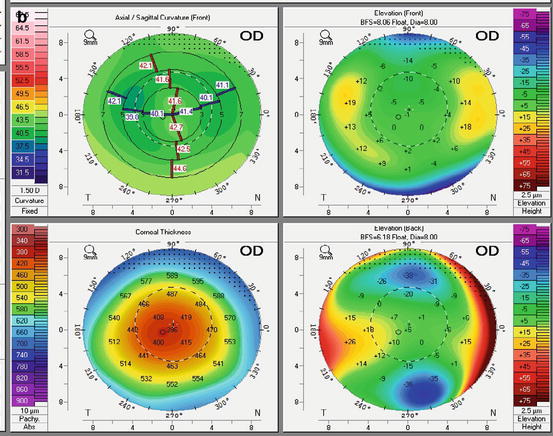

(a) Pentacam ® image of a 22-year-old male seeking refractive surgery showing thin cornea with inferotemporal steepening that was considered a contraindication to LASIK. Thus, a combined SMILE and CXL was performed. (b) Pentacam ® of the same patient 3 months postoperatively showing topographic stability and no evidence of ectasia, which was noticed in all our cases

Example 2 (Fig. 21.3)

A 24-year-old male patient having −5 sphere and −1 cylinder with a family history of keratoconus a family history of keratoconus; a factor which was considered to be a contraindication for LASIK. As a result, the decision of performing SMILE and CXL was taken.

Fig. 21.3

(a) This depicts the irregular topography of the patient’s left eye. Notably, the pachymetry map and the posterior float appear regular. (b) One month postoperative topography: inferior steepening was noticed. (c) Three months after surgery, the anterior cornea is flatter and thinner

Postoperatively, a further flattening was noticed, which we felt was due to the progressive effect of CXL and presumambly resulting in more stability over time. This pattern of progressive flatening was obseved in about 35 % of cases.

Using Corvis ® technology, mean deformation amplitude was 1.38 mm ±0.29 pre-op. One month after surgery, the mean deformation amplitude decreased to 1.19 mm ±0.29. No significant change over follow-up period occurred thereafter (for details, see Videos 2 and 3).

All cases treated so far showed topographic stability over the follow-up period up to 1 year. Figure 21.4 shows a Scheimpflug image of the cornea after combined SMILE and CXL.

Fig. 21.4

Notice the CXL demarcation line in the cornea after combined SMILE and CXL

In conclusion, simultaneous SMILE and in-the-pocket cross-linking might be a safe predictable and stable treatment option in patients where conventional laser refractive surgery is contraindicated. A delayed visual recovery associated with a transient haze formation was a temporary drawback of this procedure with the CXL regimen as described above. Further follow-up, larger samples, and different riboflavin preparations as well as application techniques have to be studied to ensure the best possible outcome of this combined procedure. Moreover, at present, we don’t know the boundaries of this approach: this needs to be elucidated in further prospective studies as shown in the following case report below.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree