Conjunctiva

The conjunctiva is a delicate mucous membrane that covers the anterior surface of the eyeball and the posterior surface of eyelids. The term conjunctiva is derived from the Latin meaning “to bind together.”

The nonkeratinized stratified columnar epithelium of the conjunctiva is two to five cells in thickness and contains mucous glands called goblet cells whose contents appear clear or bluish in routine hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) sections and are vividly periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) positive (Fig. 5-1). Goblet cells are more numerous nasally, especially in the semilunar fold (plica semilunaris).

Topographically, the conjunctiva is divided into bulbar, forniceal, and tarsal (or palpebral) parts. The bulbar conjunctiva covers the surface of the eyeball and is freely movable. The stroma or substantia propria of the bulbar conjunctiva is composed of loose, areolar connective tissue and is easily ballooned up by edema fluid (chemosis) or injected anesthetic. In contrast, the palpebral conjunctiva adheres firmly to the tarsal plate and does not move freely. Multiple gland-like epithelial invaginations or crypts called pseudoglands of Henle usually occur in the palpebral conjunctiva. The forniceal conjunctiva that arches around the superior and inferior cul-de-sacs is redundant and folded to facilitate eye movements. Several small accessory lacrimal glands of Krause are found beneath the forniceal conjunctiva, and accessory glands of Wolfring occur at the upper and lower margins of the tarsal plates. Lymphocytes and plasma cells normally are found in the conjunctival stroma and constitute part of the eye’s normal defense mechanisms.

DEVELOPMENTAL LESIONS

Congenital epibulbar dermoids are choristomatous masses that usually occur at the limbus temporally. They are composed of coarse, interweaving bundles of collagenous connective tissue and are covered by conjunctival or corneal epithelium or skin-like epithelium with epidermal appendages (Fig. 5-2A,B). Epibulbar dermoids that contain cartilage and/or ectopic lacrimal gland tissue are called complex choristomas (Fig. 5-2E). (A choristoma is a congenital tumor composed of tissue that is not normally found in an area.) Solid epibulbar dermoids should not be confused with dermoid cysts, which usually occur in the superotemporal orbit, or so-called conjunctival dermoids, which are a rare variant of cystic dermoid that occurs in the nasal orbit and is lined by conjunctival epithelium. Dermolipomas (lipo-dermoids) are solid dermoids composed largely of adipose tissue (Fig. 5-2D). These yellowish-tan, soft fusiform tumors usually are located in the superotemporal or temporal quadrants. Bilateral epibulbar dermoids and dermolipomas occur in two thirds of patients with Goldenhar syndrome (hemifacial microsomia), which also includes vertebral anomalies, preauricular appendages, and aural fistulas. Epibulbar dermoids also occur in the Schimmelpenning-Feuerstein-Mims syndrome (organoid nevus syndrome or nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn). Other congenital lesions of the conjunctiva include ectopic lacrimal gland and episcleral osseous choristoma. Episcleral osseous choristomas are plaques of mature bone that typically are located on the surface of the globe in the superotemporal quadrant (Fig. 5-3).

CONJUNCTIVITIS

Most inflammatory diseases of the conjunctiva are treated medically and are rarely seen in the ophthalmic pathologic laboratory except as scrapings or smears.

Conjunctivitis can be acute or chronic and can be caused by numerous infectious or noninfectious agents including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoans. Allergy is another important cause of conjunctivitis.

The clinical manifestations of acute conjunctivitis include redness (conjunctival injection or hyperemia), chemosis (conjunctival edema), and exudation. The exudate in acute purulent bacterial conjunctivitis contains numerous polymorphonuclear leukocytes (Fig. 5-4). Histologic sections (obtained incidentally) show edema and infiltration of the conjunctival epithelium and substantia propria by polys and an exudate composed of a mixture of polys, fibrin, mucus, and necrotic cellular debris. Clinically, the

presence of copious quantities of pus (hyperacute conjunctivitis) should suggest the possibility of gonococcal infection.

presence of copious quantities of pus (hyperacute conjunctivitis) should suggest the possibility of gonococcal infection.

Inflammatory membranes or pseudomembranes can develop in severely inflamed eyes. These adhere to the conjunctiva and are composed of fibrin and inflammatory cells. True membranes generally occur in severe disorders such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome or bacterial infections by beta-hemolytic Streptococcus, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, or Corynebacterium diphtheriae. True conjunctival membranes are firmly adherent to the epithelium, and bleeding occurs when removal is attempted.

Conjunctival pseudomembranes are less adherent and can be peeled without bleeding. Pseudomembranes may complicate infection by adenovirus 8 (epidemic keratoconjunctivitis or EKC) and adenovirus 3 (pharyngoconjunctival fever or PCF). They also form in patients with certain severe bacterial infections (Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Neisseria meningitidis, Pseudomonas, coliforms) or complicate chemical burns, foreign bodies, benign mucous membrane pemphigoid, or ligneous conjunctivitis.

Ligneous conjunctivitis is a rare form of chronic pseudomembranous conjunctivitis that is marked by a massive accumulation of fibrin that occurs in patients with type I plasminogen deficiency (Fig. 5-5). The term ligneous refers to the firm, woody consistency of the large masses of fibrin that comprise the pseudomembranes. Ligneous conjunctivitis typically occurs in children but may recur in adults. Treatment is often challenging because the inflammation is persistent and the pseudomembranes often recur rapidly

after excision. Histopathology shows two components: granulation tissue and sheets of intensely eosinophilic acellular amorphous material, which has been shown to be composed predominantly of fibrin by immunohistochemical stains (Fig. 5-5B,C). The mass of fibrin also incorporates other serum components such as immunoglobulin. The granulation tissue component (like all granulation tissue) is rich in acid mucopolysaccharide ground substance. Lesions that resemble those found in the conjunctiva can affect other mucous membranes including the larynx, vagina, and ear. Some children also develop occlusive hydrocephalus. Ligneous conjunctivitis is an autosomal recessive trait caused by mutations in the gene for plasminogen on chromosome 6q26.

after excision. Histopathology shows two components: granulation tissue and sheets of intensely eosinophilic acellular amorphous material, which has been shown to be composed predominantly of fibrin by immunohistochemical stains (Fig. 5-5B,C). The mass of fibrin also incorporates other serum components such as immunoglobulin. The granulation tissue component (like all granulation tissue) is rich in acid mucopolysaccharide ground substance. Lesions that resemble those found in the conjunctiva can affect other mucous membranes including the larynx, vagina, and ear. Some children also develop occlusive hydrocephalus. Ligneous conjunctivitis is an autosomal recessive trait caused by mutations in the gene for plasminogen on chromosome 6q26.

Acute anaphylactic conjunctivitis is marked by the abrupt onset of severe conjunctival edema (chemosis), mild injection, and itching (Fig. 3-5B). The latter is an important clinical symptom of ocular allergy. The release of inflammatory mediators such as histamine and serotonin by mast cells in the substantia propria causes the signs and symptoms in persons who are sensitized to antigens such as ragweed pollen or animal dander. Such atopic individuals produce IgE that is incorporated into the cell membranes of the mast cells. Mast cell degranulation occurs when the appropriate antigen is re-encountered. The release of vasoactive substances markedly increases the permeability of conjunctival vessels, which leads to an outpouring of fluid that fills the areolar substantia propria of the bulbar conjunctiva causing chemosis. Contact hypersensitivity to topical medications can cause severe ocular injection, itching, and eyelid erythema in postoperative patients.

CHRONIC CONJUNCTIVITIS

Chronic follicular conjunctivitis and chronic papillary conjunctivitis are the conjunctiva’s two basic patterns of response to chronic inflammatory stimuli. Chronic follicular conjunctivitis represents a reactive follicular hyperplasia of the population of lymphocytes that normally resides in the substantia propria. This lymphoid hyperplasia can be a reaction to a variety of stimuli. Conjunctival follicles are evident clinically as gray-white, round to oval elevations with an avascular center (Fig. 5-6A). Microscopically, the substantia propria contains an intense basophilic infiltrate of benign lymphocytes and plasma cells that often contains follicular centers (Fig. 5-6B). The conjunctival epithelium overlying the lymphoid follicles is often thinned.

Conjunctival follicles occur in some types of acute viral conjunctivitis. They are typically observed in acute adenovirus infections like EKC and PCF, herpes simplex virus (HSV) conjunctivitis, swimming pool conjunctivitis (Newcastle virus), and the acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis caused by enterovirus 70.

Infectious causes of chronic follicular conjunctivitis include trachoma, psittacosis, Moraxella, and infectious mononucleosis. Chlamydia, which are small obligate intracellular parasites that are sensitive to antibiotics, cause trachoma, inclusion conjunctivitis, psittacosis, and lymphogranuloma venereum.

Trachoma, a conjunctival infection, is one of the three most important causes of blindness in the world. Six million individuals who constitute 15% of the world’s blind have been blinded by the sequelae of trachoma. Trachoma is caused by serotypes A, B, and C of Chlamydia trachomatis. In endemic areas, the infection spread by direct contact with infected ocular secretions. Extreme poverty, poor hygiene, and insect vectors such as flies contribute to the spread of the disease.

Trachoma is marked by bilateral keratoconjunctivitis, which may be asymmetric. The initial infection involves the conjunctival epithelial cells and stimulates epithelial hyperplasia. Conjunctival smears stained with the Giemsa stain show a mixed inflammatory exudate, which contains both lymphocytes and polys as well as large macrophages laden with phagocytized cellular debris called Leber cells. The conjunctival epithelial cells contain diagnostic

basophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions of Halberstaedter and Prowazek (Fig. 5-7). More specific direct immunofluorescent tests and a dipstick immunoassay designed for field testing also are available.

basophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions of Halberstaedter and Prowazek (Fig. 5-7). More specific direct immunofluorescent tests and a dipstick immunoassay designed for field testing also are available.

An intense infiltration of the substantia propria by chronic inflammatory cells follows the initial epithelial infection. Numerous lymphoid follicles occur on the upper tarsus. In florid cases, the follicles develop central areas of necrosis that can extend superficially forming small ulcerations. Follicles also occur in the fornix and at the limbus. In the latter stages of the disease, the remnants of follicles may be evident at the limbus as saucer-like depressions called Herbert pits. As the disease progresses, papillary hypertrophy of the conjunctiva supplants the follicular response. Pannus formation is another characteristic feature of trachoma. The inflammatory pannus of trachoma is marked by a downgrowth of subepithelial vessels from the superior limbus that destroys Bowman membrane. Scarring occurs in the late stages of trachoma. A linear scar called Arlt line, which extends across the upper tarsus parallel to the lid margin, is one of the diagnostic criteria for trachoma listed by the World Health Organization. (Other diagnostic criteria include lymphoid follicles on the upper tarsus, a vascular pannus, and active limbal follicles or Herbert pits. Two are diagnostic.)

Blindness in trachoma typically results from sequelae that develop in the cicatricial stage. Severe conjunctival drying and epidermalization result from the loss of epithelial goblet cells and obstruction of the ducts of the main and accessory lacrimal glands. Lid scarring also causes entropion and trichiasis that predispose to severe corneal scarring as well as corneal ulceration and secondary bacterial infection.

Serotypes D through K of Chlamydia trachomatis cause inclusion conjunctivitis or paratrachoma in developed countries. Inclusion blennorrhea, an infantile form of inclusion conjunctivitis, is an important cause of acute purulent conjunctivitis or ophthalmia neonatorum in the newborn. (Other causes include N. gonorrhoeae and a chemical conjunctivitis caused by Credé silver nitrate prophylaxis against gonococcal infection.) Infants acquire the disease from an infected mother during passage through the birth canal. Inclusion conjunctivitis is a venereal disease in adults. In contrast to the superior conjunctival involvement found in trachoma, which has superior tarsal involvement, the follicles in inclusion conjunctivitis occur in the lower fornix.

Chronic follicular conjunctivitis can also be a response to cosmetics, topical medications such as atropine, eserine or 5-iodo-2′-deoxyuridine, viral particles shed by a molluscum contagiosum on the eyelid margin, or the feces of crab lice infesting the lashes (Phthiriasis palpebrarum). The lids and lashes should always be carefully (and expeditiously!) examined when unilateral follicles are encountered during clinical exam.

Papillary hypertrophy is the second relatively nonspecific reaction that occurs in some patients with chronic conjunctivitis (Figs. 5-8 and 5-9). Papillary hypertrophy typically develops on the tarsal conjunctiva and is marked by proliferation of the conjunctival epithelium and hyperplasia of the substantia propria. Pale avascular valleys that contain deep infoldings of conjunctival epithelium separate individual papillae, which have a richly vascular stroma and a central tuft of blood vessels (Fig. 5-9B). This contrasts with lymphoid follicles, which typically are avascular. Papillae contain a moderately intense infiltrate composed of a variety of inflammatory cells. Eosinophils and mast cells usually are present, and the sheets of lymphocytes and follicular centers found in chronic follicular conjunctivitis are absent.

Giant papillae, which have been likened to cobblestones, occur on the superior tarsus in vernal conjunctivitis, a bilateral chronic recurrent disease that typically afflicts adolescent males who have a history of atopy (Fig. 5-9). The term vernal reflects the characteristic exacerbation of signs and symptoms that occurs in the spring. Itching is a characteristic symptom. Patients have a thick, ropy chewing gum-like mucus rich in eosinophils and

Charcot-Leyden granules. The latter is termed the Maxwell Lyon sign. Conjunctival smears contain eosinophils and eosinophilic granules. The large “cobblestone” papillae may abrade the cornea producing painful shield-like ulcerations of the superior corneal epithelium. A limbal variant of vernal conjunctivitis marked by papillae at the superior limbus also occurs. “Limbal vernal” is said to be more common in black patients. Horner-Trantas dots, which are intra- and subepithelial collections of eosinophils and cellular debris, occasionally occur near the limbus. Histopathologically, vernal conjunctivitis is characterized by papillary hypertrophy of the conjunctiva. The edematous fibrovascular core of the papillae contains an infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells and numerous eosinophils.

Charcot-Leyden granules. The latter is termed the Maxwell Lyon sign. Conjunctival smears contain eosinophils and eosinophilic granules. The large “cobblestone” papillae may abrade the cornea producing painful shield-like ulcerations of the superior corneal epithelium. A limbal variant of vernal conjunctivitis marked by papillae at the superior limbus also occurs. “Limbal vernal” is said to be more common in black patients. Horner-Trantas dots, which are intra- and subepithelial collections of eosinophils and cellular debris, occasionally occur near the limbus. Histopathologically, vernal conjunctivitis is characterized by papillary hypertrophy of the conjunctiva. The edematous fibrovascular core of the papillae contains an infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells and numerous eosinophils.

Giant papillary conjunctivitis occurs in long-term wearers of hard and soft contact lenses and even ocular prostheses. Probably a cell-mediated hypersensitivity reaction stimulated by the accumulation of immunogenic material on the surface of foreign material, giant papillary conjunctivitis shares similarities with vernal conjunctivitis but usually has fewer eosinophils.

Phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis is thought to be a hypersensitivity reaction to bacterial proteins. In the past, it classically was associated with tuberculosis, but now, most cases probably are related to staphylococcal blepharitis. Phlyctenular conjunctivitis is marked clinically by the presence of 2- to 3- mm whitish inflammatory nodules on the bulbar conjunctiva. A zone of dilated vessels surrounds the nodules, and the overlying epithelium is ulcerated. Microscopically, the nodules are composed of acute and chronic inflammatory cells.

CHRONIC GRANULOMATOUS CONJUNCTIVITIS

A chronic inflammatory infiltrate that includes epithelioid histiocytes and inflammatory giant cells occurs in several conjunctival diseases. Discrete noncaseating granulomas are found in biopsies from patients with sarcoidosis (Figs. 3-7B and 5-10B). The granulomas may be evident clinically as small yellowish-tan nodules in the inferior fornix or epibulbar surface (Fig. 5-10A). Extensive subepithelial infiltration by sarcoidosis can stimulate symblepharon formation. The conjunctiva can be biopsied when sarcoidosis is suspected clinically and a tissue diagnosis is required. About 50% of bilateral conjunctival biopsies performed on patients known to have sarcoidosis were positive in one study, despite the absence of obvious nodules or ocular inflammation clinically.

Granulomatous conjunctivitis with associated regional lymphadenopathy, usually a preauricular node, constitutes Parinaud oculoglandular syndrome. The differential diagnosis of Parinaud oculoglandular syndrome is rather extensive and includes a number of relatively rare infectious disorders caused by variety of microorganisms including bacteria, spirochetes, Chlamydia, Rickettsia, fungi, and viruses.

Cat scratch fever is a relatively common cause of Parinaud oculoglandular syndrome (Fig. 5-11). The disease is caused by Bartonella henselae, a recently characterized bacterium that usually is inconspicuous in routine Gram stains because it is only faintly gram negative. The infected conjunctiva contains an intense infiltrate of histiocytes with foci of necrosis. The Warthin-Starry silver stain often reveals masses of bacteria in the necrotic areas. There usually is a history of a cat scratch that typically does not involve the eye or face. Conjunctival involvement results from a bacteremia. A focal angiomatous response to Bartonella called bacillary angiomatosis has been reported in the conjunctiva of immunosuppressed patients. Granulomatous conjunctivitis in response to the irritating hairs or setae of certain species of caterpillars is called ophthalmia nodosa. The setae occasionally migrate into the anterior chamber causing severe intraocular inflammation.

Synthetic fiber granuloma is a foreign body giant cell reaction to a “fuzz ball” of synthetic fabric fibers lodged in

the inferior conjunctival fornix (Fig. 5-12). Most cases have occurred in infants and young children. Synthetic fiber granuloma has been confused with ophthalmia nodosa histopathologically. Particulates of inorganic delustering agent incorporated into the fibers to opacify them and knife chatter marks on the ends of sectioned fibers serve to differentiate the synthetic fabric fibers from hair or caterpillar setae. The condition is also called teddy bear granuloma after the source of the fibers in some patients.

the inferior conjunctival fornix (Fig. 5-12). Most cases have occurred in infants and young children. Synthetic fiber granuloma has been confused with ophthalmia nodosa histopathologically. Particulates of inorganic delustering agent incorporated into the fibers to opacify them and knife chatter marks on the ends of sectioned fibers serve to differentiate the synthetic fabric fibers from hair or caterpillar setae. The condition is also called teddy bear granuloma after the source of the fibers in some patients.

Allergic conjunctival granuloma is a bilateral condition marked by the presence of yellowish nodules on the ocular surface, which is thought to be response to parasitic infestation, probably by nematodes. Histopathology discloses granulomatous inflammation and eosinophilia centered around intensely eosinophilic deposits of antigen-antibody complexes called the Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon. Nematode fragments are identified histologically in less than one fifth of cases.

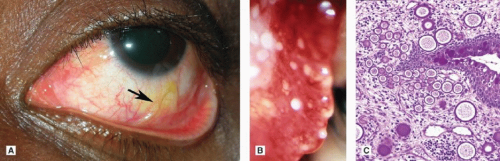

Parasitic and mycotic infections of the conjunctiva are rare in the United States. Adult Loa loa worms that have migrated to the subconjunctival space occasionally are found in visitors from West and Central Africa (Fig. 5-13A). These worms cause itching, pain, and the disconcerting sensation of a mobile foreign body. Systemic infestation with Trichinella spiralis (trichinosis) causes fever, eosinophilia, periorbital swelling, edema of the eyelids and conjunctiva, and subconjunctival hemorrhages and petechiae. Rhinosporidium seeberi, an unusual fungus with a pathognomonic histologic appearance, causes strawberry-like papillary conjunctival granulomas that are studded with white microabscesses (Fig. 5-13B,C). Although rhinosporidiosis has been reported in the United States, most cases occur in India and Southeast Asia. Microsporidia and Pneumocystis carinii can cause conjunctivitis in patients with HIV/AIDS (Fig. 4-17).

Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid (OCP) is a systemic autoimmune disease with ocular and systemic manifestations. A type II hypersensitivity reaction, OCP is thought to occur when environmental factors, probably viruses, stimulate genetically susceptible individuals to make autoantibodies (IgG) directed against epithelial basement membrane zone components including the beta 4 subunit of alpha 6 beta 4 integrin and laminin 5 (epiligrin) (Fig. 5-14). Similar diseases also occur in some patients receiving topical medication or as a paraneoplastic effect of nonocular cancer. Antibody deposition and complement activation cause chronic inflammation and stimulate fibroblasts to produce collagen causing abnormal conjunctival scarring. Conjunctival bullae rarely form in OCP. Progressive cicatrization causes foreshortening of the conjunctival fornices, symblepharon formation, and drying due to compromise of lacrimal gland and

meibomian gland ductules. The end stage of the disease is marked by epidermalization of the cornea and conjunctival epithelium and adherence of the lids to the globe. Routine conjunctival biopsies are nondiagnostic; specialized immunohistochemical procedures are required to show immunoglobulin or complement deposition in the epithelial basement membrane. These must be performed on fresh frozen-sectioned tissue.

meibomian gland ductules. The end stage of the disease is marked by epidermalization of the cornea and conjunctival epithelium and adherence of the lids to the globe. Routine conjunctival biopsies are nondiagnostic; specialized immunohistochemical procedures are required to show immunoglobulin or complement deposition in the epithelial basement membrane. These must be performed on fresh frozen-sectioned tissue.

Severe subepithelial fibrosis, symblepharon formation, severe ocular drying, and trichiasis complicate Stevens-Johnson syndrome (erythema multiforme), which is thought to be a type III hypersensitivity reaction to microbes or drugs characterized by circulating IgA containing immune complexes and lymphocytic vasculitis. Conjunctival involvement by pemphigus vulgaris is marked by intraepithelial bulla formation; therefore, subepithelial scarring and symblepharon formation do not occur. In pemphigus vulgaris, autoantibodies are directed against desmoglein 3, a protein component of desmosomes joining epithelial cells.

The normal reparative phase of the inflammatory response is marked by the production of granulation tissue, which plays an important role in wound healing. An inappropriate, exuberant proliferation of granulation tissue may develop on the surface of the globe or conjunctiva after surgery or trauma. Ophthalmologists apply the thoroughly ingrained term pyogenic granuloma to these relatively common inflammatory tumors. Ophthalmic pathologists diagnose these lesions as “exuberant granulation tissue” (“pyogenic granuloma”) to distinguish them from an acquired type of capillary hemangioma called pyogenic granuloma by dermatopathologists. (The latter lesions usually are relatively devoid of inflammatory cells and rarely occur on the conjunctiva or eyelid.)

The richly vascular mass of exuberant granulation tissue typically has a smooth, rounded surface and is red or pink in color (Fig. 5-15). A paler hue may reflect superficial necrosis or adherent exudate. These lesions often arise quite rapidly, which serves to differentiate them from true neoplasms.

The richly vascular mass of exuberant granulation tissue typically has a smooth, rounded surface and is red or pink in color (Fig. 5-15). A paler hue may reflect superficial necrosis or adherent exudate. These lesions often arise quite rapidly, which serves to differentiate them from true neoplasms.

The mass of granulation tissue is composed of proliferating capillaries, activated fibroblasts with contractile properties called myofibroblasts, and a spectrum of acute and chronic inflammatory cells including polymorphonuclear leukocytes, lymphocytes, plasma cells, histiocytes, and occasional eosinophils and mast cells (Fig. 4-20). The inflammatory infiltrate usually lacks epithelioid histiocytes and inflammatory giant cells unless it harbors residual lipogranulomatous inflammation from a previously drained chalazion. The vessels in pyogenic granuloma usually radiate from the base or stalk of the lesion. This radial vascular pattern and the prominent inflammatory cell component differentiate pyogenic granuloma from hemangioma on histopathologic examination.

DEGENERATIONS

Chronic light exposure damages the stromal connective tissue of the bulbar conjunctiva exposed in the inter-palpebral fissure. This actinic damage is evident clinically as a yellowish- or gray-white opacification of the subepithelial tissue. In advanced cases, a raised yellowish mound called a pinguecula forms near the limbus (Fig. 5-16A). Microscopy discloses an acellular grayish granular deposit of extracellular matrix material beneath the limbal epithelium, which usually is elevated and thinned (Fig. 5-16B). Some pingueculae contain thickened vermiform fibrils of degenerated collagen; others contain deposits of hyaline material like those found in chronic actinic keratopathy. The damaged matrix material stains positively (black) with the Verhoeff-van Gieson stain for elastic tissue (Fig. 5-16C). Pretreatment with the enzyme elastase does not abolish positive staining for elastic tissue. Hence, the term elastoid is applied. The degenerative process actually may involve the production of abnormal elastic tissue components (elastodysplasia) by light-damaged fibroblasts. Similar foci of elastotic degeneration often are found in pterygia.

Conjunctival amyloidosis usually is a localized phenomenon that occurs in healthy adults who do not have systemic amyloidosis (Fig. 5-17). The degeneration can involve any part of the conjunctiva. The subepithelial amyloid can form circumscribed polypoid, yellowish, waxy nodules on the epibulbar surface or may diffusely infiltrate the substantia propria. Intralesional hemorrhage is often found. Light microscopy discloses relatively acellular amorphous deposits of eosinophilic hyaline material. Special stains, usually Congo red, and polarization microscopy are used to confirm the diagnosis. Conjunctival amyloidosis is often composed of immunoglobulin light chains.

CONJUNCTIVAL CYSTS

Conjunctival cysts occur congenitally or may develop secondarily when surface epithelium is entrapped or implanted in the stroma during surgery or trauma. Conjunctival inclusion cysts are lined by conjunctival epithelium, which may be attenuated. The lumen appears empty or it may be filled with mucinous material and/or proteinaceous fluid. Cysts also form when conjunctival crypts or pseudoglands of Henle become occluded and dilate. The proteinaceous luminal contents of such cysts occasionally undergo inspissation and even calcification, forming irritating concretions that literally feel like “grains of sand” in the eye. Another type of conjunctival cyst is caused by the blockage of an accessory lacrimal gland duct. Such cysts are analogous to sweat ductal cysts of eyelid skin. They have a clear empty lumen and are lined by a dual layer of ductal epithelium.

CONJUNCTIVAL NEOPLASMS

There are three basic categories of conjunctival neoplasm. The great majority of benign and malignant tumors of the conjunctiva arise from the squamous epithelium, associated melanocytes, or the lymphoid cells that normally reside in the substantia propria.

SQUAMOUS EPITHELIAL LESIONS

Squamous epithelial lesions of the conjunctiva include benign papillomas, actinic keratoses, and the spectrum of ocular surface squamous neoplasia (OSSN) that begins as intraepithelial neoplasia and can progress to invasive squamous cell carcinoma (Figs. 5-18, 5-19, 5-20, 5-21, 5-22, 5-23). Rare keratoacanthomas of the conjunctiva have been reported. Bilateral benign leukoplakic lesions occur on the conjunctiva and other mucous membranes in hereditary benign intraepithelial dyskeratosis (Fig. 5-24).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree